What to Do If You Actually Kinda Hate Yourself

You probably aren’t a garbage human!

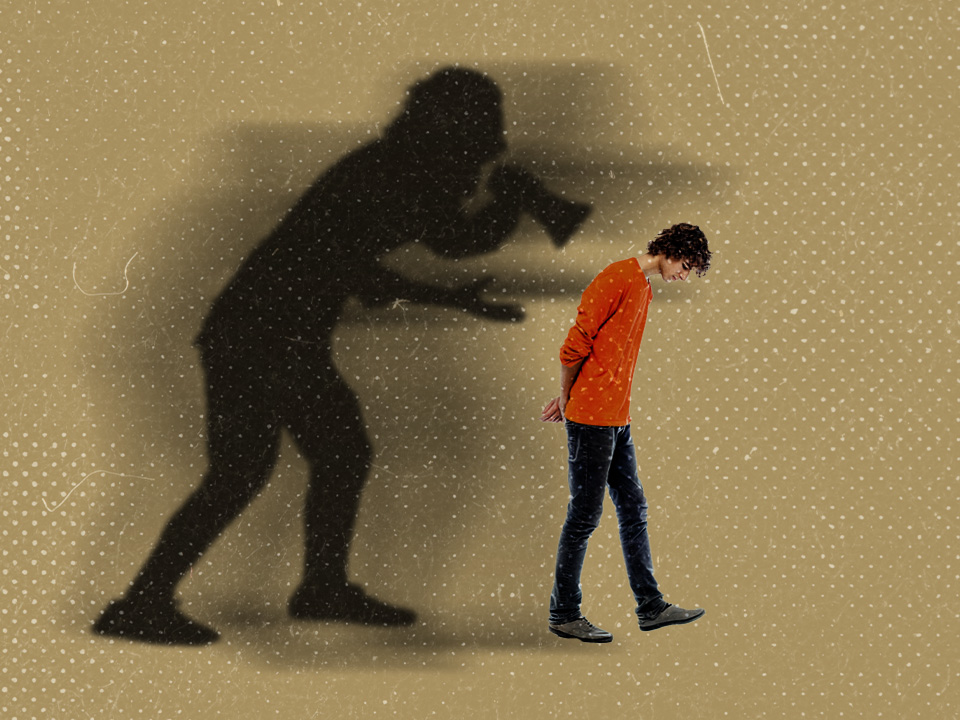

If you often find yourself thinking, Ugh, I hate myself, when shit goes wrong, then you get it.

Self-hatred is a tough mental state to exist in. Oftentimes, it shows up as an intense inner dislike, feelings of shame, negative thoughts (I hate myself or I’m not good enough), low self-worth, and isolation, says therapist Emily Myhre, LCSW. And for some people, that self-hate mindset can be hard to shake, Myhre explains.

While lots of circumstances can lead to self-hatred (also called self-loathing), people who hate themselves generally believe that something is wrong with them, says therapist Allyson Sproul, LCSW, CAADC.

Sometimes that belief stems from adversity we faced growing up (see: bullying, harsh parenting, racism, etc.), Sproul says. When we can’t explain why bad things or traumas happened to us, we often blame ourselves. That can feed into self-loathing too, Myhre says. As we get older, if we feel like we’re not living up to a certain standard, we can feel bad about who we are. Over time, those thoughts and feelings can lead to self-hatred, Sproul explains.

Regardless of your upbringing or past experiences, self-hatred can be more common in those dealing with mental health concerns like depression, addiction, or body dysmorphia, says Sproul.

However you got here, being stuck in this cycle can feel pretty hopeless, but you can work toward a healthier sense of self over time by addressing the symptoms that fuel self-loathing. That progress won’t be quick, since you’re likely undoing decades of negative thought patterns, says Myhre. Still, every small step will get you closer to where you want to be and further from where you are now. Below, therapists explain exactly how to do that.

1. Find the origins of your negative self-talk.

Finding out where your self-hatred comes from can help you actually do something about it. Myhre suggests getting to the root cause by asking yourself: When I talk down to myself, whose voice does it sound like? Is it my parents’ or random trolls’ online? Is it a new voice or an old voice? When you know where that voice is coming from, it gets a little easier to counteract it.

2. Reframe your thoughts.

Like we said, negative thoughts about ourselves stoke self-hatred. So, by trying to make these thoughts more neutral, we can lower the volume on the hate, says Sproul. Take an idea like, I can’t do anything right. You can reframe it as something like, I’m human, and not everything I do is perfect. It’s not super positive, but it’s a more realistic take on whatever went wrong. Ditto for tweaking, Why does everyone hate me? to something more realistic like, I'm not for everyone, just like not everyone is for me. You’ll probably find that neutrality is easier for a self-hating brain to believe than a positive affirmation like, I’m the best!!!!, says Myhre. It’s not as big of a jump.

You can also try editing your rude self-talk to be less blame-y, suggests Sproul. So that might look like, That didn’t go well, instead of, That didn’t go well because I’m an idiot. Again, that reframe isn’t optimistic, but it also doesn’t belittle you for existing. Baby steps.

3. Put your thoughts on trial.

Another way to lessen the impact of self-deprecating thoughts is to challenge them. A lot of the time our negative internal dialogue is irrational, meaning there’s no actual evidence to support the rude things we’re saying. Unfortunately, that doesn’t stop us from believing them anyway, says Myhre. However, when you make an effort to disprove those thoughts, it’s easier to see them as distorted and untrue.

Say you’re thinking, I fail no matter what I do. Ask yourself if that’s definitely the case. Was there ever a time you didn’t fail, even if you weren’t totally successful? If nothing comes to mind, ask people you trust for their perspective, suggests Myhre. You can text them something like, “I’m in a bad headspace and thinking all I do is fail. Heeelp! Do you remember a time when I actually didn’t fuck up?” Spoiler: They do.

4. Practice gratitude.

By making an effort to notice what you’re grateful for, you’re training your brain to think more positively. And the more you practice finding the good in what’s around you, the easier it is to identify goodness in yourself, Myhre explains. (Also, it helps that gratitude is shown to boost your overall mood, she adds.)

So, set a reminder to think about a few things you’re grateful for (even if it’s your halfway-decent cup of coffee), Myhre says. Keep doing that until it becomes easier for you to notice nice things unprompted. That’ll help you start to recognize the positive things about yourself.

5. Consider what’s actually in your control.

When you’re in a self-hate cycle, blaming yourself for everything can become a habit—even if you did nothing wrong, notes Myhre. So when you’re in the thick of that, try to objectively analyze the entire story or problem and see how much is really your fault.

The next time you start to beat yourself up for your boss’s passive-aggressive comment—because you suck, so obviously you did something wrong—try this out: Open a Google doc or use a pen and paper to write the story from beginning to end. Then, review it and get really skeptical about how much you contributed to the problem. Don’t be surprised if you find that you’re not the only one to blame, Myhre says.

6. Tap into your confidence.

As we’ve said, when you hate yourself, you think negatively about You. But doing something you’re good at helps you switch into a more positive frame of mind (without having to be all “I love myself” in the mirror). You feel confident, in control, and maybe even a little happy, Sproul says.

To get out of self-hate mode, break out a puzzle you know you’ll crush, cook a recipe you always nail, or make a playlist your friend will love. Whatever activity feels like an easy target is fair game.

7. Own up to your mistakes.

Guilt is definitely appropriate when you’ve effed up, but self-hatred can make you hold onto that feeling and ruminate about being a horrible person. In that case, forgiving yourself and making amends can help you release the shame a bit, says Myhre. That’s because owning up to your mistakes proves that you’re worthy of forgiveness and you can learn from your mistakes. “Self-hatred hates that because it wants to keep you [feeling horrible],” Myhre says.

Of course, forgiving yourself isn’t easy when you feel like an awful person. So try some self-compassion by reminding yourself that humans make mistakes, says Myhre. You can also ask yourself, If someone else did the exact thing I did, would I treat them this way? (Probably not.) Then, apologize to whomever needs to hear it and commit to showing them you’re sorry by changing how you act, Myhre adds.

8. Examine your coping skills.

Sometimes people dealing with self-hate turn to unhealthy coping mechanisms (like self-harm, overspending, or substance use) as a form of punishment or because those things feel good in the moment, Myhre and Sproul say. Unfortunately, those behaviors usually cause more shame, which leads to more self-hatred, they note. Finding positive ways to cope (like going for a walk, taking a soothing shower, talking to someone, or letting yourself feel your feelings) can break that cycle. If you’re having a hard time shifting your coping skills on your own, a therapist can help you figure out why and can support you as you make changes, says Sproul.

9. Seek help.

Depending on what your self-hatred stems from, you might want to look for a therapist who specializes in trauma therapy, body image issues, substance use, or family and relationships. Once you land on a therapist, they can “help you understand how you're thinking, how you're behaving, and the impact that has on your life,” says Myhre. “There's nothing you can't say to us, truthfully, that we haven't heard, or, even if we haven’t heard it, we're never going to judge you for it.”

Wondermind does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Any information published on this website or by this brand is not intended as a replacement for medical advice. Always consult a qualified health or mental health professional with any questions or concerns about your mental health.